Our Obsession with Mental Well-Being is Making Us Sick

How the self-care climate incentivizes suffering and undermines mental health

*Note: The ideas presented here serve as the foundation for a series of upcoming pieces offering a more in-depth analysis of the issues outlined.

by Rebekah Wanic with Nina Powell

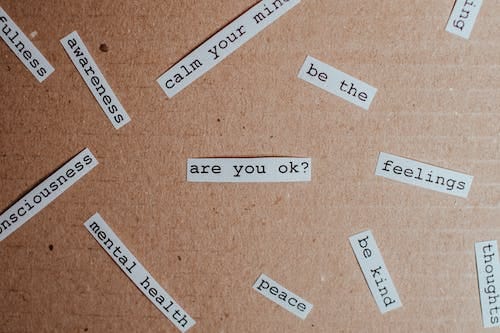

All around us, in schools, at the workplace and via mainstream media, we are bombarded by the psychology industrial complex with messages about the importance of prioritizing mental health and the need to check in with ourselves and others to assess psychological well-being. On face, a shift to increased promotion of self-care and increasing awareness of, and access to, effective treatment for psychological distress seems like a positive - a move that demonstrates prosocial motives and progressive kindness. However, like so many well-intended movements that start with correcting an oversight, this focus has morphed into a disproportionate overcorrection, resulting in a mindset shift that is deeply damaging to individuals and society.

For much of history, there has been strong stigma associated with mental illness. In the past, many who should rightly have been cared for were left on the margins of society without a means for advocacy or redress. In arguably more time than it should have taken, the plight of the mentally ill finally began to enter the larger consciousness, treatment options started to expand, and movements to destigmatize mental illness began to take hold. This change has prompted better and more effective care and increased access to beneficial services for many. This is a positive.

Unfortunately, the slippery slope of acceptance has become an avalanche of overcorrection with near constant presentations and campaigns designed to promote mental health awareness and prioritize psychological well being above all else. Additionally, data continue to show higher and higher levels of (self-reported) suffering, particularly for anxiety and depression. The pandemic seems to have accelerated this focus. It is time to take a step back and question whether our obsession is now undermining the very mental health it sought to protect by encouraging us to search for suffering and rewarding us when we find it.

The Search for Suffering

One consequence of mental health obsession is the push to constantly ask ourselves and others whether we are ok. This question turns one inward, to evaluate their own experience. Inherent in asking, however, is the suggestion that one might not be ok. And, the more frequently the question is asked, the more likely it is that it will reach someone at a time when they are not, given that a normal part of human experience is emotional fluctuation. A person taking stock while annoyed because of a work hassle or irritated at their child for spilling some juice will focus in on this normal and temporary negative emotion, making it paramount, and now the featured lens through which to judge one’s well-being.

Everyone experiences stress. Everyone experiences periods of negative emotions. These are part of what it means to be human. They are also necessary parts, quite often, of experiences that bring us fulfillment and growth. Being frequently asked to take stock of such feelings while being trained to be wary of them means that one will notice and dwell on them more. This inward focus works to increase the perceived burden of the experience and keep one in the moment. And, when such emotions and perceptions are identified in the search for well-being, which is increasingly (although wrongly) defined as the absence of all hardship, they are much more likely to be problematized instead of valued or at least tolerated.

The Reinforcement Machine

And what then? What does one do when pushed to the self-realization that they are not ok, that they are stressed or sad or worried? We are encouraged to seek assistance from the myriad of resources provided by the psychology industrial complex that have been funded (or are available if one has their own financial backing) to support the crisis of mental ill health. For those truly suffering, this is a good thing. But, we should pause to consider the ways in which this cycle of help-seeking can become reinforcing.

First, we shift away from personal responsibility. In a climate awash in well-being promotion, the consequences of poor self-management that may result in stress or relationship dysfunction are turned into a psychological problem, not one derived from choice and behavior, and those around the individual must bear the burden. The problem is compounded by the lack of incentive to be “ok” because it buys you nothing. The psychologically healthy individual doesn’t get to claim identity as a sufferer and loses out on the allowances offered to those who fall into victimhood.

Consider too the way that so many celebrities have garnered attention for their “brave” disclosures about their own struggles with mental ill-health. Again, what began as a good thing - public attention to and reduction of stigma surrounding mental illness - has now become just another check box in the requirements for stardom. We have known for a long time that celebrities influence their followers and the culture at large. If young people see their idols gaining attention for their identity as sufferers, this further incentivizes them to look for their own mental struggle to claim similarity with a popular figure and reinforces a message that social benefits will accrue when they do so.

We are not arguing that all of these changes, or any of them, are in and of themselves a bad thing. Providing a bit of space and being sensitive to those around us is admirable, being sensitive to the needs of others is commendable, and offering support and medical care for those who are suffering is desirable.

However, the system of accommodations can be abused and social comparison works to encourage over-reporting of struggle. If my colleague gets time off because they are feeling worried (pathologized as anxiety) or a bit down (pathologized as depression), then why should I stay here and work when I sometimes experience such feelings too? Further, the trouble when embracing victimhood is that there is always someone who is worse off, whose suffering is greater. Those who derive much of their identity from filling the role of the downtrodden can solve this by exaggerating their symptoms or avoiding recovery. If my accommodations and allowances disappear when I am well, then what is my incentive for working to get there? Hard work begets me...more hard work. No thanks, I’ll take my duvet days. (Note that such behavior could result from conscious malingering or simply environmental cues and reinforcement.)

Lastly, many of the people who are pushing for increased awareness of mental struggle and access to treatment intend that this awareness will reveal more problems, in part because of self and financial interest. When psychologists and consultants and clinicians and therapists promote well-being, they may be well-intentioned but they also need problems to manifest so they can obtain clients, charge their fees, and justify their positions as part of the ever growing psychology industrial complex. Consider how many awareness campaigns remind us of the masses suffering without help - and connect us with those who can for a fee.

A Set of Simple Solutions

So, what do we do? We begin by ceasing the obsessive focus on mental well-being. Given that calls to raise awareness and provide treatment occur with too great of frequency, conditioning us to constantly take stock of our mental temperature, we should begin by reducing this attention. Further, since the current climate prioritizes mental well-being over all else and encourages the pathologization of normal experience, we must change this narrative. We should work to cultivate a healthier mindset, one that allows us to develop skills to navigate the ups and downs that are part of normal life experience with greater resilience and ceases to incentivize suffering. We should reward those who demonstrate mental toughness and stop providing ever increasing concessions to those with minor psychological complaints. We note here that this is possible to accomplish this while still providing support for those with clinical need.

We should shift attention toward fostering programs of empowerment, those that empower agency by teaching people personal responsibility, relationship building skills, resilience and health promotion from a young age. It is essential that we stop pathologizing the range of human emotion and we re-orient ourselves to valuing, rather than maligning, the stress and struggle that comes with working hard. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this boils down to a psychologically-derived solution. It is a mindset shift away from the incentivization of suffering that is necessary to promote better mental health for all.

https://psnews.com.au/comcare-boss-stresses-governments-focus-on-psychological-safety-in-the-aps/122675/

Also the concept of psychological safety in the workplace is becoming enshrined across the Australian public service